When Russian soldiers entered the village of Yahidne, in northern Ukraine’s Chernihiv region, Halyna*, 59, and her husband were in their home. The soldiers ordered them to undress and surrender their phones. Then as the soldiers took over their house, the couple was forced into the basement of a nearby school, carrying almost nothing with them.

It was March 2022. Russia’s full-scale invasion was just beginning and the extent of it was still unclear. “I thought that they were just going to play with us for a day, no more. And then they would let us go home,” said Halyna. “But when we came to the basement, I saw that no, that is it, we are not here for one day.”

More than 300 residents of the village were forced to stay in the school basement without adequate food, medicine or basic amenities. The space measured only around 190 square metres, so there was not enough room for everyone to sit, let alone lie down. While there, the residents had no communication, light or heat, and their clothes remained constantly damp due to condensation and poor ventilation.

The school janitor, Ivan, said the most challenging part was explaining the situation to the children:

“The older kids understood everything on their own. But the youngest, just one and a half months old, cried constantly. Her mother did not have milk. We could not always boil water to feed the baby. We were fortunate if we could even get water from the well. There were times when we had to collect rainwater.”

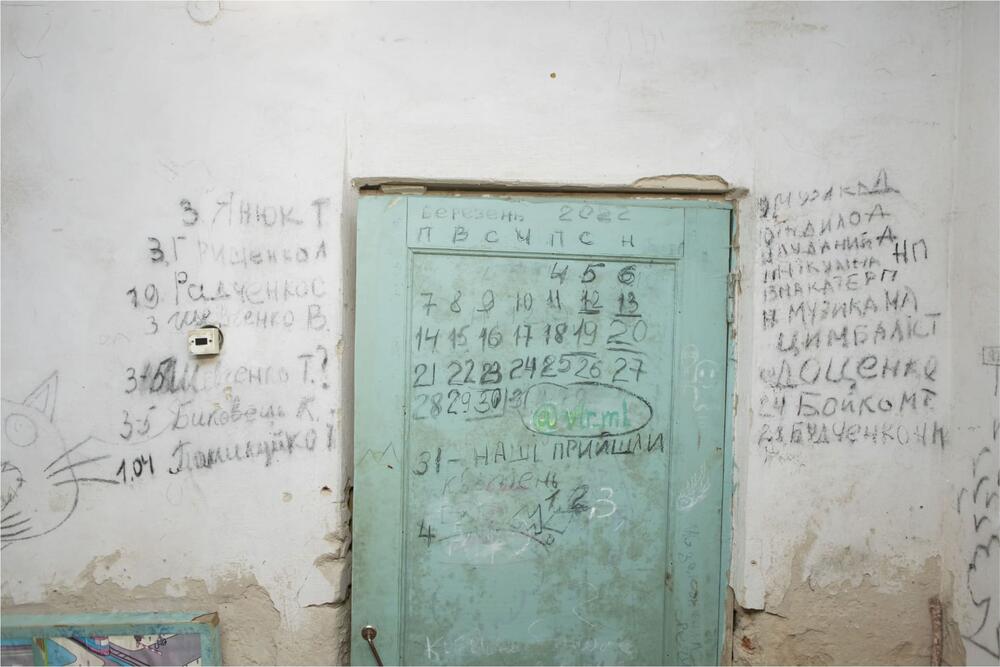

More than 50 children were among those forcibly held in the basement. In order to distract them from the terrible conditions, makeshift play areas were set up and the walls were turned into canvases for drawing.

The residents also used the walls to record their time underground. When the Ukrainian Government finally regained control over the village and released them from the basement, the wall showed that 27 days had passed and 10 people had died.

Now, two years later, the consequences of the war and occupation in Yahidne continue to be felt. Not only have homes and streets been destroyed, but the residents who were detained are still scarred by the memories of what they endured. “

I cry all the time,” said Halyna, recalling how the Russian soldiers repeatedly threatened her with violence and physically assaulted her husband. “The wound has not healed yet. Even when I go to the garden, I am afraid. I dig in the beds and then look up to see if Russian soldiers are coming out of the forest. I cannot forget their faces.”

To help respond to this psychological trauma, UNFPA-supported Mobile Survivor Relief Centres have been sent to Yahidne and other formerly occupied Ukrainian villages that experienced human rights violations like forced detentions and conflict-related sexual violence.

Olha Boyko, a psychologist with the Survivor Relief Centre, said the ongoing mental strain of war makes recovery even more challenging. Many survivors like Halyna continue to live in the places where the trauma occurred and are constantly confronted by reminders of their pain.

“Many do not understand why this happened to them. Almost everyone has physiological symptoms resulting from the trauma they endured. There is also the fear that it could all happen again,” said Ms. Boyko. “That is why it is important to visit these communities, talk to the people, create an atmosphere of trust, and convey that they are not alone, that support is close”.

Meanwhile, everything in the school basement remains as it was two years ago, though no classes have been held in the building since.Many of the children who were forcibly confined there still live in Yahidne and play on the ruined school grounds, where empty boxes of Russian ammunition can sometimes be found.

During a visit to Yahidne, Liudmyla Burseva, a child psychologist from the UNFPA-supported Survivor Relief Centre, conducted a therapy session with local children. She said they were the most challenging group she had ever worked with: “They do not have experience trusting adults. They have not had positive experiences of believing in themselves and their abilities. But the most important thing is that after our session, the children left with positive emotions and a sense of achievement. It is crucial that such activities are held regularly for these children.”

The ability to carry out visits to areas of Ukraine that are no longer under Russian occupation has been made possible by the new operational format of the SRCs. In April of this year, the network of Survivor Relief Centres received three vehicles, enabling specialists to assist war-affected Ukrainians in frontline regions who are unable to visit stationary SRCs.

Two mobile Survivor Relief Centres, funded by the Spanish government, operate in the Kherson, Kyiv, Chernihiv, and Sumy regions. Another, funded by the Belgian government, operates in the Kharkiv region. The mobile centres are fully equipped to provide consultations.

The Survivor Relief Centres were established to respond to the challenges of the war. They offer support to people who have experienced captivity, survived occupation, are internally displaced, or are in need of assistance, including those affected by conflict-related sexual violence.

Psychosociaal, legal, and informational support at the Centres is provided confidentially, free of charge, and without conditions. The first Survivor Relief Centre opened in Zaporizhzhia in July 2022. As of today, these services are available in 12 cities: Kyiv, Dnipro, Lviv, Kharkiv, Kherson, Odesa, Poltava, Kropyvnytskyi, Chernivtsi, Sumy and Mukachevo.

UNFPA is committed to continuing to work together with the Government of Ukraine and partners to support people in small communities, particularly through the work of the Survivor Relief Centres.

The Survivor Relief Centres were established through the initiative of the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister for European and Euro-Atlantic Integration, with the support of the Government Commissioner for Gender Policy, in partnership with UNFPA, the United Nations Population Fund in Ukraine, and with financial support from the governments of Austria, Belgium, Spain, and Sweden, in collaboration with local authorities.

*name changed for safety

Photograpgher: Yevhen Zavhorodnii