"When I returned to Irpin in April, the city seemed like a ghost town” psychologist Victoria Semko found Irpin empty and destroyed in April 2022, after the city returned to the control of the Ukrainian government.

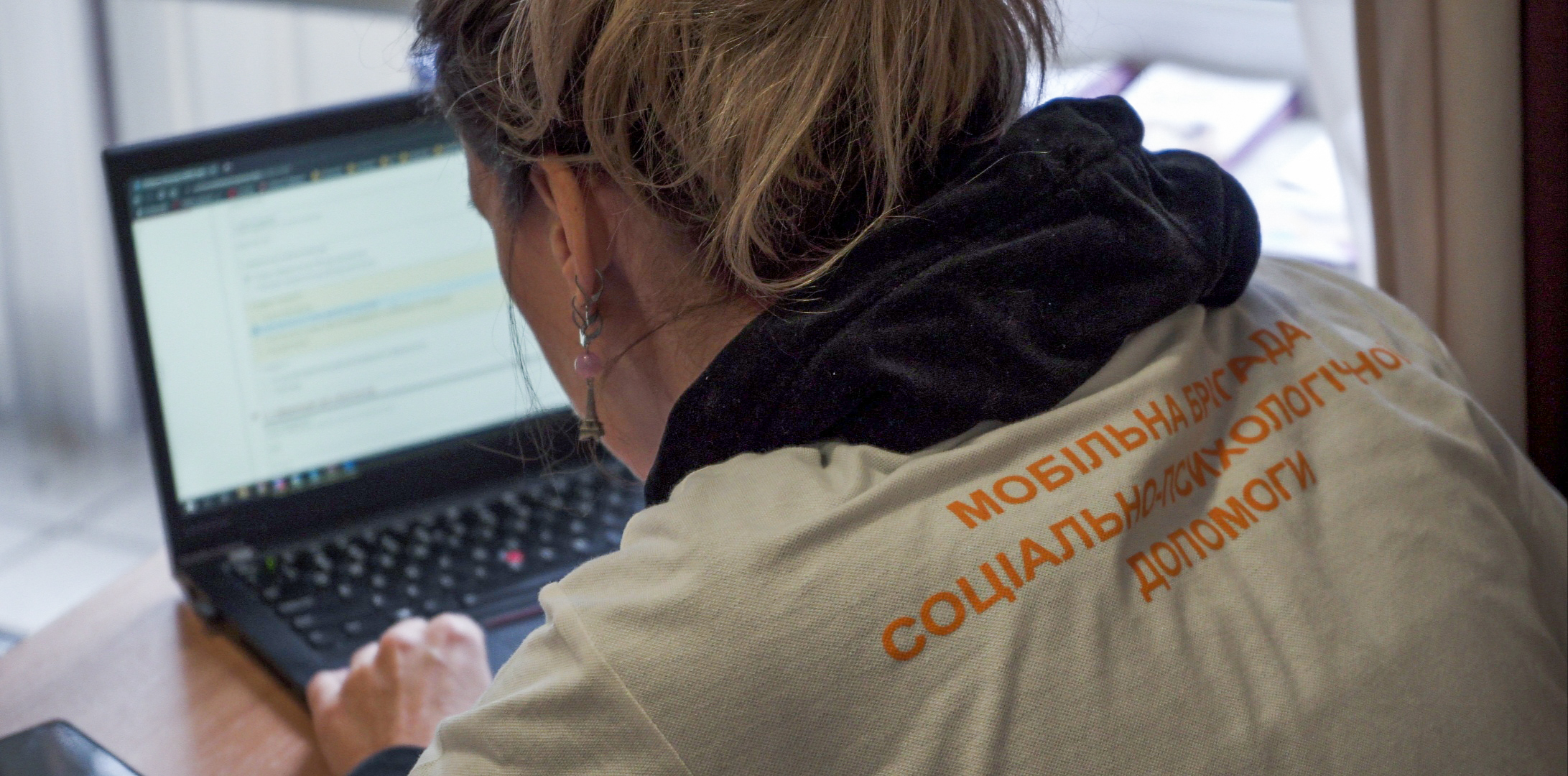

Her daily life, as well as her hometown, changed radically. After returning to Irpin, Victoria began to provide psychological support to all those who needed help. In the summer, she became a head of the social-psychological support mobile team launched by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), with the support of USAID. During this time, hundreds of consultations were held and dozens of women received support.

The psychologist told UNFPA about the kind of help requested most often, the changes she notices in how people feel and how the war affects Ukrainians generally.

"I came to my senses after a week"

At 5 a.m. on February 24, psychologist Victoria Semko started the car and, with her niece, left Irpin in the direction of Truskavets in the Lviv region. She had no idea that the war had started at that moment. She was on her way to pick up children from a camp. The first sounds of explosions overtook her on the way.

She could no longer return. Irpin came under the temporary control of Russia. But as soon as the city returned to the control of Ukraine, Victoria immediately returned.

"When I first came back to Irpin, it was scary. There were shot cars and burnt tanks on the streets. The city was emptied. Absolutely everything was different. The city seemed like a ghost," recalls Victoria Semko.

Her house was damaged, as was the school where her children studied. Because of this, says Victoria, she felt depressed.

" It took me a week to come to my senses, restore my personal psyche, and decide what to do next. I took matters into my own hands and started a psychological support group in Irpin. Later, I was invited to work in the UNFPA socio-psychological assistance mobile teams," says Victoria.

"40 percent of appeals relate to domestic violence"

As soon as the social and psychological assistance mobile teams started working in Irpin and Bucha, with support of USAID, Victoria and her colleague started receiving calls.

"The first call was from a local resident, Olesya. She had not left Bucha since the first day of the war. Even after the city returned to the control of Ukraine, she did not make contact with anyone for a very long time, because she was hiding. She was afraid; she did not know that the city was free. When she talked about what she had experienced, it was clear that she was holding back her emotions. But later, in a conversation with us, she let this pain come out, talking about it. She had survivor trauma and the trauma of a witness, because she had seen so many atrocities with her own eyes. We helped her express these emotions," says the psychologist.

And there are many people, like Olesia, who needed support because of war-related trauma. About 30 percent of appeals to the mobile team in Irpin and Bucha come from people who are experiencing the loss of a loved one or the loss of their home during the war. Many are experiencing serous trauma, because their men or children are fighting.

"Recently there was an incident that I will remember for a long time. A woman approached us. Her son fought in the Kherson region and there was no contact with him. She said that she was constantly crying. Even at work, teaching children at school, during breaks she ran to the bathroom or looked for an empty place to cry. If at school it happened only during breaks, then at home continuously. She was worried that he might die, or get captured. She was in such a state that I also shed tears several times during our meeting. However, I pulled myself together, because the outcome of our consultation depended on it. We talked about all her fears: what might happen. We discussed how to deal with it, how to adapt, how much her son's fate also depends on her, and how her son needs her to be healthy. Next time she told me: "Victoria, you did something to me, I became completely calm." She even pasted up written notes in her house: ‘I am calm’, ‘I believe in a positive outcome’. They became her support and a reminder that she should be strong," recalls Victoria.

The most frequent appeals related to gender-based and domestic violence. Forty per cent of calls concerns it, Victoria says. Mostly clients complain of psychological violence, being sworn at and humiliated in every way.

When mobile teams get a call, they quickly go out to the survivors. Their main task is to stabilize the emotional state of clients. Each mobile team includes a psychologist and a social worker. In addition to psychological support, they can redirect survivors, help them move away from the abuser to a safe place, help them to receive legal, medical, material or other help, for example, in employment or changing profession.

"War gave permission for people to work with a psychologist"

Because of the war in Ukraine, the mobile brigades had to work with new challenges, says Victoria Semko. For example, there were appeals from women who went abroad at the beginning of the full-scale war, and when they returned, they were met with violence from their husbands.

"The husband believed that his wife had deprived him of the opportunity to participate in raising the child while the mother, saving the child, took her abroad," says Victoria.

Because of severe stress and worry about the fate of their relatives, some clients begin to drink alcohol more often. Several times, mobile teams had to take clients to shelters, because they could not leave the woman alone with the abuser.

There were also cases when women became addicted to alcohol.

"We had a case when a woman stopped drinking alcohol. We helped her get a job with another client of ours who has her own sewing workshop. This was part of a cycle of help," Victoria recalls.

According to the psychologist, it is increasingly necessary to work with people’s emotional exhaustion. If in the first months of the war there was stress and a surge of energy, an urge to fight, it was followed by exhaustion and apathy. The first signs of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are already beginning to appear in some of those affected by the horrors of war.

"A person works, everything is fine, but when he or she starts talking about being under the temporary military control of Russia or about the evacuation, they start crying. People talk about flashbacks, pictures that keep coming to mind. But now people have become more open to working with a psychologist. The war seems to have given them permission to work with a psychologist. Now there are more and more requests from both women and men," says the psychologist.

Another positive change that Victoria notes is that people increasingly understand the difference between a psychologist and a psychotherapist.

"Every healthy person who has experienced some communication problems, in the family, at work, in personal life, with children, should contact a psychologist. We often encounter situations when they turn to a psychologist when there is already a complete crisis in terms of all basic needs," says Victoria.

"I feel my calling"

Before working in the mobile brigade, Victoria worked as a psychologist for 10 years and says that only with the beginning of the full-scale war she fully feels her calling.

"First of all, thanks to psychology, I was able to help myself change my vision of the world from that of a survivor of violence to being the creator of my own life, and I am now happy to share this experience and help other people. It is extremely pleasing when I see positive changes in the people I work with," says Victoria.

The psychologist believes that it is important to talk to people about the different types of violence. She fears that the level of domestic violence may increase in the context of the war. So people need to know what they are dealing with.

"There is a huge number of military personnel in the country now. Returning from the combat zone, their hormonal system works in a completely different way. At the frontline, it is poised to act, to save life, but after returning, there is a decline, and the soldiers need something to compensate for the hormone rushes that they are used to having at the frontline. These outbursts can lead to irritation, and sometimes even uncontrolled outbursts of aggression. This does not only happen to those who return from the frontline. We all feel anger at the enemy, but we cannot all direct it at our attackers. A substitute mechanism is activated. And often people unknowingly divert their irritation, anger, aggression onto their loved ones, usually onto those close to them and those who are weaker. And it is very important to talk about it, to explain ways of understanding emotions and , how to direct them in the right way," says the psychologist.

To receive help from the social and psychological assistance mobile team in the city of Irpin and Bucha, call the following numbers:

+380505275653

+380961415258

Contact details of for mobile teams in your city are on the UNFPA and "Break the Circle" websites.

Mobile teams work with the support of UNFPA, in coordination with the Office of the Vice Prime Minister for European and Euro-Atlantic Integration of Ukraine, the Ministry of Social Policy of Ukraine, and with the financial support of the Governments of the United Kingdom, Canada, the United States, and of the Humanitarian Fund for Ukraine (UHF).

The mobile brigade in the city of Irpin works with the financial support of the USAID Bureau of Humanitarian Assistance.

The material was created with the support of the USAID Bureau of Humanitarian Assistance. The opinions, views, and recommendations expressed in this video do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of UNFPA or the US Government.

"There are more and more requests for psychological help” — how the UNFPA mobile team works in Irpin and Bucha