For Yevhen, 32, who lives in Kherson, active leisure has been an everyday way of life since his early years. Swimming, fishing, kayaking and spearfishing are just some of the hobbies the man had when he was a child. Since graduating from school, he has been working in industrial climbing and, for four years now, owned the city wake park. For various leisure activities and for the habit of active recreation, which became the foundation of his lifestyle, Yevhen is grateful to his father; now he himself tries to follow those rules in raising his own children – Maria, 8, and Sashko, 3.

"It is the right thing to do, to have your children accustomed to active exercise, because it contributes to the health of the nation. I notice it even in myself, how childhood experiences get chiselled in memory and how they come back in adult life. At some point, my father taught me how to water-ski behind a boat, so four years ago I decided to develop the wakeboarding community and eventually teach that sport to my children,” Yevhen tells.

So Masha, the man’s daughter, overcoming her fear with her dad’s help, tried to master waking when she was as young as four; last year she finally started waking on her own. The younger, Sashko, is a real fidget, says Yevhen – he began to show interest in waking when he was only two, try on his father's gear, and even riding the board with his father.

After founding a children's wakeboarding school, the man spent more and more time with other people's children, while his wife took care of their daughter and son. According to Yevhen, lack of time for his own family made him feel uneasy. Therefore, as soon as Yevhen learned that the UN Population Fund established a club for dads in Kherson, which, among other things, organised leisure for dads with children, he joined the club right after the first meeting.

"For me, TatoHub has become a magic kick in the rear"

"TatoHub has become a magic kick in the rear to make me pay more attention to my own children. I came to the club because they organise really cool leisure activities, which I would hardly do in my everyday life. Like a pizza-baking master class, which was interesting both to me, and to my children. Or, together with my son, we made a Christmas wreath, and the little one then boasted to everyone that he had made it with his father," the man shared.

Besides, according to Yevhen, a great benefit of participating in the club activities is the exchange of experiences with other dads: "You see how other parents treat their children, you borrow something from them, you also prompt some things to others."

UNFPA began to create the TatoHub network way back in 2020. In early 2022, 12 clubs were functional, offering fathers opportunities to spend quality time with their children, communicate with male psychologists and discuss any challenges in parenthood.

According to the man, the dads’ club in Kherson had regular meetings every two weeks. Together with other dads, Yevhen discussed the organisation of activities for children and parents that could be useful for both children and adults. One of those was held by the club in Yevhen's wake park.

"We taught parents and children how to swim and board. Children looked and learned from their fathers. In fact, this is one of the ways for dads and children to bond – through shared hobbies," the man says.

The war disrupted the usual pace of family life

This summer he was going to put Sashko on the board, but plans that this family had, as well as those of millions of other Ukrainians, were destroyed by the war. Yevhen's hometown was captured by the Russian troops in a matter of days. He says he could not have imagined that could happen in the 21st century until he witnessed the events himself.

Yevhen recalls that in the morning of February 24, he had no idea of what to do next. Having analysed the circumstances and made a stock of food and fuel, the family decided to stay in their native Kherson.

"I realised that the roads would be clogged, and on the news there were reports of attacks on cities in Central and Western Ukraine, so we had no idea where we could go," the man recalls.

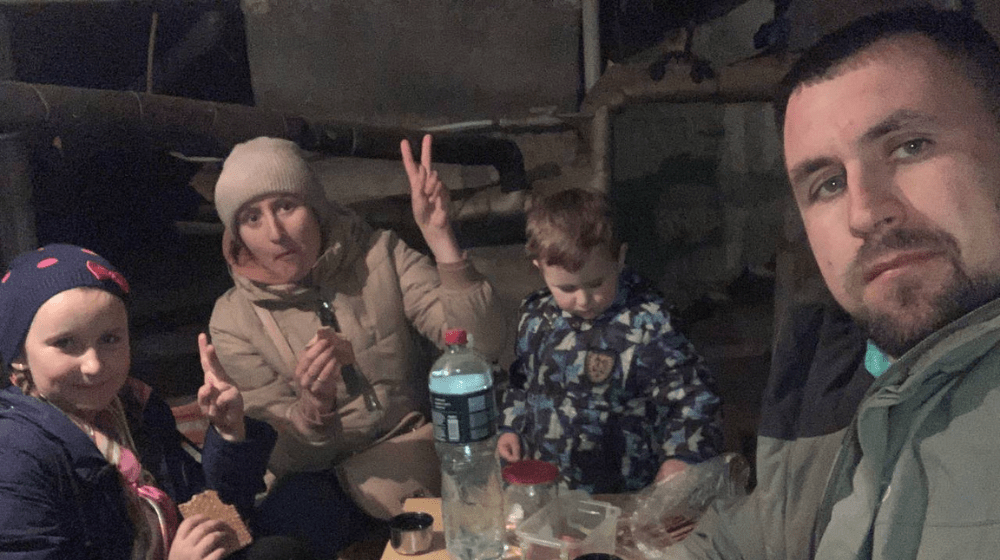

Yevhen's family stayed in the occupied city for 52 days. The first week, the man tells, his wife and children did not leave the house at all, just regularly went to the bomb shelter.

At first, the couple explained to the children that the air raid alarm signals were military exercises. In a while, however, it became clear that it was a new reality. Children began to associate the alarm sirens with the need to go to the shelter, where there were many other kids to play with, says Yevhen.

"My son and daughter know that this is a war. They may not fully understand what it really means. Fortunately, they did not experience all its horrors, as in Bucha, Kharkiv, Mariupol. We only heard the explosions. Of course, the children got scared and cried, but my wife and I reassured them that they were far away. Sometimes we put them to sleep in the bathroom, behind two walls, for safety," Yevhen shared.

Over time, the situation in Kherson grew more difficult, when there emerged shortages of fuel, food and medicines, says the man. "Life in the city meant standing in a line. For several hours, you wait for bread in one queue, and then, in another queue, you wait for milk," says Yevhen. In addition, almost all local residents lost their jobs.

Although the war has become a major disruption to the TatoHub network, most of them continue to work today. Many have expanded their area of activity and are now are helping families, distributing humanitarian aid, and TatoHub psychologists provide consultations for both men and women. A great emphasis today is placed on therapeutic games with children, especially those who have seen the horrors of war. For example, TatoHubs continue to work in the occupied Kherson and Nova Kakhovka; in Kramatorsk, the hub joined the local association "Everything will be fine" and actively helps to respond to the humanitarian crisis; however, the hub in Rubizhne, which also covered Severodonetsk, is currently closed, because its leader Andriy died in March. TatoHubs in Odessa, Vinnytsia and many other cities work with pregnant women, providing them with hygiene kits and the help of psychologists.

We left with the realisation that we are leaving for a long time

In April, the family made a difficult decision - to leave their hometown. At that point, as Yevhen says, they already realised that the situation was there to stay. Despite the absence of formal routes for evacuation from the Russian-occupied Kherson, long waiting lines and the risk of being shelled, Yevhen's family was lucky to leave the city "relatively easily." The family's car was spared thorough searches by the military, and the waiting time for them was only three hours. The couple and their children currently live in Ternopil.

According to Yevhen, the children easily adapted to the changes, in particular due to the efforts and support of their parents who tried to adjust their whole life in a new place to old habits.

"The daughter attends needlework classes for displaced persons. She made new friends. With the younger one, we have a new tradition - to go to the public artesian well to fetch water. My wife and I overlook their daily routine to make sure everything is the way it was at home. We are gradually getting ready for the upcoming school year, and organising a school and a kindergarten", Yevhen shares.

The man himself is already considering the possibility of launching sports development projects in Ternopil. He says that there are possibilities to do wakeboarding in the city, but it is difficult to implement from the financial standpoint, because all park equipment was left behind in the occupation.

Despite the fact that the family left their whole life in Kherson, the couple try not to lose their positive attitude and support each other by talking. "We let everything go, left it behind. We pray it survives. Ternopil is a beautiful, well-groomed city with many parks and playgrounds. But we will wait until peace comes, Ukraine will return and we can go home," the man hopes.

Tatohub.Kherson was opened in the framework of the “EU 4 Gender Equality: Together against gender stereotypes and gender-based violence” programme, funded by the European Union, implemented jointly by UN Women and UNFPA.