After Ukraine lost control over the city of Kherson, the social workers who remained there did not stop their work. A shelter for survivors of domestic violence continued to operate secretly. Women and girls continued to receive help. But the shelter was looted before the city was returned to the control of the Ukrainian government.

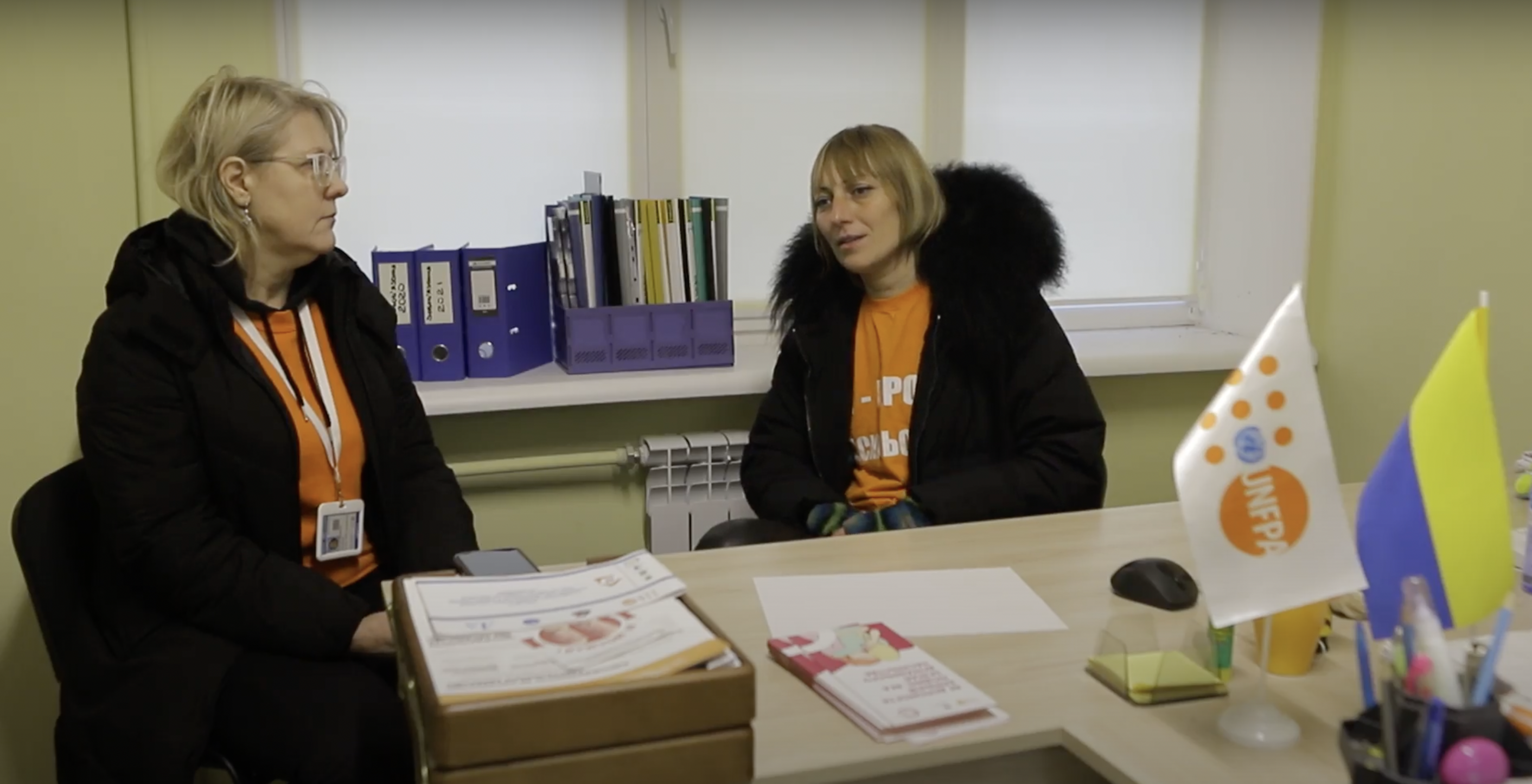

UNFPA visited the shelter and spoke with its managers about how they managed to support everyone in need for 10 months.

"I understood that the employees would not stop working under any circumstances"

"The war for me, as for everyone, started unexpectedly. My mother-in-law woke me up around 6:30 am. She said that her eldest son, who lives in Kyiv, had called her and told to evacuate urgently, because the war had started, and Kyiv was already under fire. At that time, in peaceful Kherson, it was not believable. I turned over and went back to sleep, but just a few minutes later I heard a very powerful explosion and realized that it was no joke," Anton Yefanov, head of the Kherson city centre of social services for families, children and youth, describes his February 24.

First of all, Anton and his wife gathered for a family meeting. The key question: what to do next? But the decision was not made immediately, because as well as the family, it was necessary to take care of dozens of other important people in Anton's life – employees and clients of the Mother and Child Centre and the Crisis centre for survivors of domestic violence. Both institutions housed women who needed help.

"I understood how confused they were and that employees would not leave their posts under any circumstances. At about 10 in the morning, we realized that fighting was going on outside the city. Frontline fighters were flying over Kherson, shelling the city. We did not know whether we could evacuate or how safe it was to travel on the roads. There was chaos in the city. Long queues formed at gas stations and supermarkets. We decided immediately to go to the wholesale centre where we bought goods for the Сrisis centre. The owner of the warehouses gave us a lot of products, realizing that it was most likely that he would get paid money for them," says Anton Yefanov.

Thanks to this, women and children living in a Shelter for survivors of domestic violence and a Mother and Child Centre had a supply of food. In addition, they provided clients with warm things and medicine and developed a plan for how to act if the situation were to worsen.

Personal considerations were set aside.

"My wife is a driver, but she was very afraid to drive alone. I was afraid to go with her, because I was worried that I would not be able to return to Kherson, or that I would not have enough inner strength to go back to the city. But it was necessary to return, because all my employees, everyone who needed us, stayed here and worked as a single mechanism. So we stayed and this was the right choice," recalls Anton.

"At first the shelter worked secretly"

After the Centre for survivors of domestic violence was opened in Kherson in 2019 with the support of UNFPA and the Governments of the United Kingdom and Canada, it provided assistance to dozens of clients.

Photo: 2020 year

"Some women's stories will be with us forever. I rarely cry, but there is a story from which I could not hold back tears. We tried to help a woman from Mykolaiv. Her friends simply snatched her from her son's arms. He was killing her. She had great difficulty reaching us, we followed her every step, and when she finally got to us, entered the shelter, we all cried. It was touch and go all the way. This was her child, that she had cradled, loved and in whom she invested a lot of time, energy and love, but unfortunately, drugs had ruined her son's life, and hers too. It was scary," recalls Natalia Kraska, head of the Crisis centre for survivors of domestic violence in Kherson.

Photo; Natalia Kraska (2020 year)

The shelter became an island of safety for women. There they could live, receive help from a psychologist and a lawyer, renew their documents, and feel they were among like-minded people.

Furthermore, the city built a system for response to and prevention of gender-based and domestic violence. The police, doctors, social services were all working towards a common goal – to be a means to change the lives of survivors.

"The women trusted us, so they constantly turned to the shelter. Even at the beginning of the full-scale war, the centre had clients," Natalia Kraska recalls.

Because the address of the institution was kept secret, the Russian troops were not aware of its work.

"This was free Ukraine territory that no one knew about. The Russian troops did not know about the shelter. But some employees of the city council and regional administration who switched to the Russian side did know about our work before the full-scale war. But they did not have enough human resources to "take us on". They were chiefly concerned with getting higher positions for themselves in occupation institutions. There was a kind of interdepartmental competition," recalls Anton Yefanov.

The premises of the shelter were not closed until Anton and Natalia had worked out where to relocate the clients so that they would be safe. They had to do this because the Russian military had set up one of their administrative institutions opposite the shelter.

"I have never felt so defenceless, neither as a person nor as the head of an institution. We had occupation troops outside our windows all the time, people were constantly receiving Russian roubles there. At that time, it became extremely dangerous to be in the shelter. We decided to evacuate all three shelter clients to the Mother and Child Centre. Of course, we also had to take care of the clients of the Mother and Child Centre, because their funding stopped on February 25, and at that time there were eight clients with children who needed food and water," says Natalia.

Photo: Natalia Kraska, 2022 year

"Domestic violence is not a problem for Russian army"

Natalia Kraska recalls that survivors of violence became defenceless when Ukraine lost control in Kherson.

"The police were not in the city from the first day, so there was nobody to rely on in cases of domestic violence. Those services that were working did not consider domestic violence as a problem," says the head of the Crisis centre for survivors of violence.

Natalia Kraska saw this in the case of one of her former client. Thanks to the shelter, she had been able to leave her ex-husband, but because of the war, she started communicating with him. Over time, the man started to abuse her again, and then, out of desperation, she was forced to turn to the Russian police but was refused help.

"Many abusers became more aggressive. They understood that they could be unpunished. This client found my phone number, contacted us, and thanks to the support of UNFPA, we helped her leave Kherson and now she is receiving help in Kyiv," says Natalia Kraska.

Another source of help for women when the city was under the temporary military control of Russia was hospitals, which continued to operate.

"The problem was that people were afraid to go to doctors, there was a fear of the occupation authorities, of the military, what they would find out, especially in cases of violence by Russian troops. We were incredibly grateful when we received kits for women and girls who had survived sexual violence related to war. We secretly supplied all the hospitals with these kits so that, in case of need, they could provide urgent help," says Natalia.

"The shelter was robbed"

After the clients of the shelter moved to the Mother and Child Centre, the premises were closed. Once or twice a week, Anton and his colleagues visited the shelter to check its condition.

Thanks to the security system that all shelters have, they entered through the backup entrance without turning on the lights or attracting attention. During one of these visits, they noticed that a TV had disappeared from the wall in one of the rooms.

“I took the key and went to the front door to try to open the lock from the inside, but it had already been changed. We realized that someone had been there before us. On the table near the reception, we noticed a paper's folder that had not been there before. So as not to expose ourselves to danger, and not to make it clear that we were there, we just photographed documents that were inside. The papers contained everything — names, surnames, positions, who came here, why, where they planned to go next. These were the decisions and orders of the occupation authorities, with the original signatures of the executors. It seems that they were so preoccupied with stealing the TV that they simply forgot these documents," says Anton Yefanov.

The same evening, Anton decided to take all the equipment from the shelter, so that it would not fall into the hands of thieves. But this time the main entrance was already open, and all the equipment was being taken out of the building.

"I managed to photograph the cars in which all this was being taken, to photograph the licence plates of the cars. I called my father and in his car we followed those who had robbed the shelter. We recorded that all the stuff was taken to one of the subdivisions of the Kherson City Council, which at that time was in the hands of the occupiers. After the city returned to the control of Ukraine, I found out that they took almost all the looted equipment from all communal institutions of the city to this place," recalls the head of the Kherson city centre of social services for families, children, and youth.

Anton handed over all this data to the Ukrainian law enforcement officers and blocked the shelter's doors so that it would not be damaged any more.

"There was a feeling of powerlessness. So much effort was invested in this centre, so much soul. You can't even call it a robbery, there was a feeling that you were losing a part of yourself," Yefanov says.

"As soon as the city returned to the control of the Ukraine government, we started preparing to restore work"

Dark rooms, empty but carefully made beds. For the first time in many weeks, the lights are on in the shelter, and what previously did not attract attention becomes more noticeable: the dusty space around the places where there was equipment and cables instead of surveillance cameras. But in their usual places there are still the flags of Ukraine, Canada, and the United Kingdom, which financed the opening of the shelter. The flags seem frozen in space and time. No one has touched them since the last female clients left the shelter.

For the first time since February 24, the management of the shelter entered the building. And immediately held a joint meeting about restarting work. Mykolaiv mobile police teams working with cases of domestic violence came to the meeting too. It was decided that until the shelter stared fully-fledged work, Kherson social services would cooperate with Mykolaiv colleagues.

"We will restore the shelter; we are not even considering other options. We have a very well-thought-out system of interaction between all the services that provide assistance, we have a very good base. Fortunately, the walls and everything necessary to start working remained intact. Of course, many workers left the city and I understand that we should not expect them to return; , it is dangerous in the city now. But the shelter will work," says Natalia Kraska.

Until the shelter is up and running, the city's social workers are helping in the humanitarian sector, so that the people of Kherson can receive humanitarian aid as soon as possible.

The city of Kherson is a participant in the project "Cities and communities free from violence", thanks to which the city developed a system of response to and prevention of gender-based violence.

The project "Cities and communities free from domestic violence" is being implemented thanks to the support of the Governments of the United Kingdom and Canada.